Call to Action: Increasing the Number of Physicians from Underrepresented Communities as a Solution for the Need of a Culturally Competent Health Care System

Call to Action: Increasing the Number of Physicians from Underrepresented Communities as a Solution for the Need of a Culturally Competent Health Care System

By: William Mati

The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and the social problems should largely be solved by them.

-Rudolf Virchow, M.D.

When my parents migrated to the Land of Opportunities, they never imagined giving birth to a child with a strong passion in changing the face of health care. Why would they? I mean, by looks of those who practiced medicine in the U.S. at the time, it seemed as if a doctor was born, not made. Fortunately, looks can be deceiving.

According to a 2018 article published by the United States Census Bureau, the population is expected to continue to diversify throughout the 21st Century1. As is the duty of a physician to meet the needs of their patient, new demands will be brought to light in a dense, multidimensional society. By equipping the health care industry with professionals from various sociocultural backgrounds, patients can be ensured that they will establish fruitful relationships with health care providers who are working to institute health equity for all.

Why is a Culturally Diverse Population of Doctors Needed Anyways? Let’s Take a Walk Down History Lane to Find Out…

Why is a Culturally Diverse Population of Doctors Needed Anyways? Let’s Take a Walk Down History Lane to Find Out…

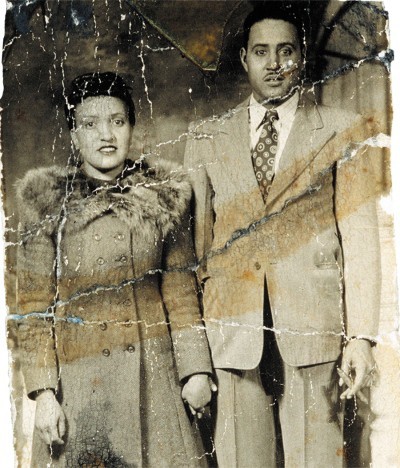

Don’t worry, the entire walk is quite long. In this case, our journey is very short: 20th Century Baltimore, Maryland — where Jim Crow ideology thrived. It is here where we find Henrietta Lacks, an African- American woman commonly known among the biomedical research community as “HeLa.”2 A wife and mother of five children, Lacks passed away due to cervical cancer without ever seeing her young grow up3. On the other hand, homogenous researchers and physicians had secretly discovered a scientific gold mine after obtaining a biopsy of Lacks’ tumor, only to exploit her children years later in hopes of further developing the new immortal cell

line from their mother. In the eyes of the medical professionals assisting Henrietta Lacks, treating her (and the family) as a test subject was justified due to the “free care” given to Lacks3. Need I say, this was all done without any initial awareness or consent from the Lacks Family.

Such ethics and treatment of minority groups — particularly African-Americans — were NOT uncommon just a few decades ago. The lack of diversity among health care professionals at the time resulted in numerous voiceless communities that were simply unable to protect themselves from harmful philosophy and medical practice. As a way of pointing toward the elephant in the room, I pose the question: “How can we be the voice of the voiceless?”

Where is the U.S. Health Care System at Today?

You may have heard the relatively new buzzword among Medical Education departments across the United States: Cultural competency. By instilling an awareness and respect for the existing diversity in humanity, it is (rightly) proposed that health equity, access to health care, and the quality of care will increase for people of all sociocultural and economic backgrounds4. Indeed, this is a large step in the correct direction (recall the demographic statistics mentioned in the beginning). However, it is not sufficient.

I was fortunate to have participated in the 2018 ChicagoCHEC Research Fellows Program, a health care pipeline program that seeks to expose underrepresented students to an array of perspectives regarding cancer health disparities5. One of the primary aims of ChicagoCHEC is to ensure that the diversity of this country is reflected in the health care industry with the hopes of institutionalizing health equity for all. In fact, by doing so not only increases the likelihood of patients feeling comfortable with their health care

providers6, it simultaneously proliferates cultural competency by introducing heterogeneity directly into the Medical field. As such, patients can feel at greater ease knowing their voices will be heard — whether it is from professionals of similar backgrounds or through the courage to speak up in a place where they feel represented. By breaking down structural barriers through programs geared toward diversifying future medical professionals, the face of health care will adjust to the needs (and wants) of all patients.

I was fortunate to have participated in the 2018 ChicagoCHEC Research Fellows Program, a health care pipeline program that seeks to expose underrepresented students to an array of perspectives regarding cancer health disparities5. One of the primary aims of ChicagoCHEC is to ensure that the diversity of this country is reflected in the health care industry with the hopes of institutionalizing health equity for all. In fact, by doing so not only increases the likelihood of patients feeling comfortable with their health care

providers6, it simultaneously proliferates cultural competency by introducing heterogeneity directly into the Medical field. As such, patients can feel at greater ease knowing their voices will be heard — whether it is from professionals of similar backgrounds or through the courage to speak up in a place where they feel represented. By breaking down structural barriers through programs geared toward diversifying future medical professionals, the face of health care will adjust to the needs (and wants) of all patients.

About the Author

William Mati is a first-generation college student studying Biochemistry at Loyola University Chicago. He was part of the 2018 ChicagoCHEC Research Fellows Cohort. William plans to enroll in Medical School during 2020 with hopes of utilizing Precision Medicine as a tool for addressing Health Disparities. (Note: Any feedback or general comments are highly encouraged and should be directed to [email protected]).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Melissa A. Simon, M.D. and the graceful ChicagoCHEC staff, community partners, and speakers who have invested their passion and time in developing the health care professionals of tomorrow. Surely, all your work is not in vain but has planted seeds that shall flourish all across Chicago and the World.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are exclusively those of the author and not necessarily representative of the organizations the author represents nor the ChicagoCHEC organization. This work is solely intended to help further disseminate information related to ChicagoCHEC’s cause and stimulate dialogue about important topics. It is not a report by ChicagoCHEC itself and must not be treated as such.

Footnotes

- Vespa, J., et al. (2018). Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/P25_1144.pdf

- Callaway, E. (2013). Deal Done Over HeLa Cell Line. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/news/deal-done-over-hela-cell-line-1.13511

- Skloot, R. (2011). The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Broadway Books. Print.

- National Institute of Health (2017). Cultural Respect. Retrieved from https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear- communication/cultural-respect

- Taylor, S. (2018). The Health Care Career Pipeline: A Program Director’s Reflection on Extending the Resources of the University to the Minority Student Community. Retrieved from https://nam.edu/the-health-care-career-pipeline-a-program-directors-reflection-on-extending-the- resources-of-the-university-to-the-minority-student-community/

- Chen, F., et al. (2005). Patients’ Beliefs About Racism, Preferences for Physician Race, and Satisfaction With Care. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1466852/